Part 1 – My Journey into change management

I first became aware of the people-side of change long before using the term Change Management. When introducing PRINCE2 project management disciplines for major technical projects in the 1990s, the whole change adoption and utilisation challenge became apparent. Being an internal OD Consultant in a corporate environment provided entry in major change projects, but usually at the point of implementation when people issues were stalling the change. Or in the recovery, after the fact. Management learning and development introduced individuals’ emotional and psychological responses to change, but rarely went further than coaching managers implementing change (usually restructures) or working on staff communications during change announcements. These ventures into project management and change leadership were insightful but insufficient. This created a compelling reason to gain entry much earlier in the life cycle of major organizational changes.

Four things strengthened my approach, value add, and credibility:

First – being a manager in an organization implementing some tricky changes, rather than always being on the design end of change that would impact others. The felt sense of the challenges and opportunities of change helped ground the value and conviction of change approaches.

Second – finding approaches tangible and practical enough to be credible in a world of change dominated by project management. For me it was Prosci Inc., who offered a framework for managing the people-side of change in projects and some quick, data-driven tools to raise awareness early in the project lifecycle.

Third – the realisation that as a change agent or consultant I do not manage change. Leaders and managers do. They have a more-powerful, longer-lasting influence and front of stage role. It was a major shift to focus on supporting them in their role and accountability. Building their change capability along the way and reducing anxiety, as a trusted advisor, with useful approaches and methods.

Fourth – development of my OD practice in whole systems change with a move from HR back to the strategy function. This lifted my arena of change to whole system transformation with behavioural and cultural dimensions, a portfolio of change initiatives, and dynamic of planned and emergent change.

All these opportunities and issues are in the Change Management mix. Practitioners need to be agile, read the context, and bring forward credible interventions.

Part 2 – What is Change Management?

The answer to this question varies depending upon whom I ask and what kind of change they are thinking about. This can be change at an individual, project, or whole system level (incremental, step change, or transformational in nature). Nearly always a mix of all of them.

At its highest level, and probably oversimplified, Change Management can be described as – ‘supporting the people-side of change’ or a collective term for all approaches to prepare, support, and help individuals, teams, and organizations in making organizational change.

The discipline of Change Management has evolved significantly over the past five decades. Sharing foundations with OD in human behaviour and psychology, it exploded onto the business scene in the mid-1990s.

- Change Management’s roots began with efforts to better understand how humans experience change and the dynamics of human systems (pre-1990s era). This period provided crucial insights, research, and frameworks for understanding successful change. Some of the primary contributors during this time included Kurt Lewin (1948), a social psychologist who introduced three states of change – unfreezing, changing, and refreezing – as well as Force Field Analysis. The formula for change (C = A × B × D > X) was created by David Gleicher, in the early 1960s, and refined by Kathie Dannemiller, in the 1980s (C = D × V × F > R), to describe the factors for meaningful organizational change to take place. William Bridges (1979) described the states of a transition as ending, the neutral zone, and new beginnings. Beckhard and Harris (1977) created the well-known, present state, transition state, and future state model. Linda Ackerman coined the phrase Change Management, and in 1968, publishing her first iteration of the nine-phase Change Leader’s Roadmap.

- During the 1990s, the discipline of Change Management entered project meetings and leadership teams. Language began to form around the discipline of Change Management to show that individual change does not happen by chance but can be supported with thoughtful and repeatable steps. Some of the most-notable contributors include General Electric (early 1990s) – introducing the Change Acceleration Process as part of its larger improvement program; Daryl Conner (1992) Managing at the Speed of Change – provided invaluable insights on numerous change concepts and coined the term burning platform; and John Kotter (1996) who in a Harvard Business Review article, and later in his book Leading Change, described eight change failure modes and subsequent steps to address them.

- During the 2000s, Change Management experienced significant formalisation, with processes and tools applying more-rigorous structure and repeatable processes. Organizations began creating specific jobs, functions, and structures to support Change Management application across the organization, such as the Change Management Office, Centres of Excellence, or Communities of Practice. Professional associations, standards, and certifications emerged during this time, such as the Change Management Institute and the Association of Change Management Professionals.

From these developments we can see Change Management described at three levels:

- For Individuals – supporting each person through their individual change journey

- For Organizational Projects and Initiatives – securing outcomes and returns on investment (ROI) by supporting impacted individuals to adopt and use solutions

- For Enterprise Change – delivering strategic intent, mitigating change saturation, and improving agility by embedding change into the fabric of the organization

At the same time change differs in the scale of its disruption to the status quo:

- Transactional – small changes in procedures, processes, practices.

- Incremental or continuous – the type of constant change in which well-managed organizations are constantly engaged in as they try to improve. Not necessarily small changes, but part of an orderly flow.

- Step – a significant change that requires an extraordinary shift in ways of working for a particular process or group of people, with planned support and management.

- Transformational – comprehensive organizational change, a combination of planned steps and emergent learning, often with behavioural and mindset challenges. This is where that infamous statistic is often quoted that nearly 70% of all change efforts fail to meet their intended outcomes.

- Radical or discontinuous – complex, wide-ranging change, often brought on by shifts in the external environment, which requires a radical departure from the status quo.

Change practitioners need to be aware of and able to move between all levels of change, shifting their focus of work and methodologies appropriately.

Part 3 – Change Management (OD by another name?)

When asked what I do, I have often found it easier to say ‘Change Management’ rather than ‘Organization Development’. Especially to a client looking for support in a difficult change. Most have some sense of what Change Management might mean, but little idea of what Organization Development is. Using the term Change Management might be easier in gaining entry, but in using it am I doing myself, OD, and the work that needs doing, a disservice?

From the beginning, OD developed and applied its theories of people and change to organizational life and functioning. Many of its interventions have now become mainstream, shaping the way we think about how organizations work. This includes Change Management, which emerged as a subfield of OD in the 1960s.

Much has changed since OD’s beginnings in the 1950s; for example, the pursuit of efficiency in the form of business re-engineering in the 1980s, rationalisation in the 1990s, and aggressive outsourcing in the 2000s. When emerging and formalising its approaches from this background, Change Management has emphasized the ‘technical’ side of change, with a mechanistic viewpoint. Informed by an often-less-conscious Newtonian view of organization, which prizes rationality, certainty, logic, and reduction to parts. This is curious, as changes leaders and managers will readily tell of the personal and people impact of poorly managed change, whilst failing to pay attention to it in their plans.

Warner Burke, in his contribution to the ‘Just in Case’ video series (from Quality and Equality Ltd.), proposes that Change Management is not Organization Development. They differ in terms of their values, source of theory behind the work, primary skill, intervention mode, change activities, and sustainment of change.

My view is that Change Management may not be Organization Development, but Organization Development can be Change Management in the way it is informed, practised, and the intent that is held. The disciplines of OD and Change Management cross paths when an organization introduces a change that needs to be effective on both the technical side and people side. They are complementary disciplines because they each provide focus, processes, and tools for supporting a transition towards a future state. The common objective, in times of change, is to improve the performance, capacity and health of the organization.

The OD Practitioner has to be aware of the dangers of being constrained and limited in the scope of their work when in a Change Management context. Whilst Change Management can be a good point of entry, the risk is that you become an extra pair of hands doing change implementation work on behalf of the client. You may gain entry with a narrow brief, but hold a more expansive view of what is possible and needed. So what perspective can OD offer and what competencies does an OD Practitioner (working in a Change Management context) need?

Part 4 – An OD perspective on Change Management

Organization Development is about change in human systems, but not just any change under any circumstances. Instead, OD theory and practice promotes several key criteria related to change efforts (Organization Development as an Evolving Field of Practice by Robert J. Marshak; Chapter One, The NTL Handbook of OD and Change):

- Change should be directed toward enhancing individual, group, and organizational capabilities, as well as the conditions under which people work and contribute.

- Change should be carried out consistent with social science knowledge about human systems and how they change, as well as a generally optimistic set of values and assumptions about people’s capability and potential.

- There must be a readiness and felt need for change in the system (at some level), and the space to raise its awareness and work it.

- Change should be initiated and led, to the greatest extent possible, by the people involved; it should be based on their assessment and concurrent with the need to change.

- Change efforts should not only lead to the desired change, but also leave a client system with increased capabilities and skills to address future situations and needs.

A dilemma in OD is what to do when one or more of these criteria are absent.

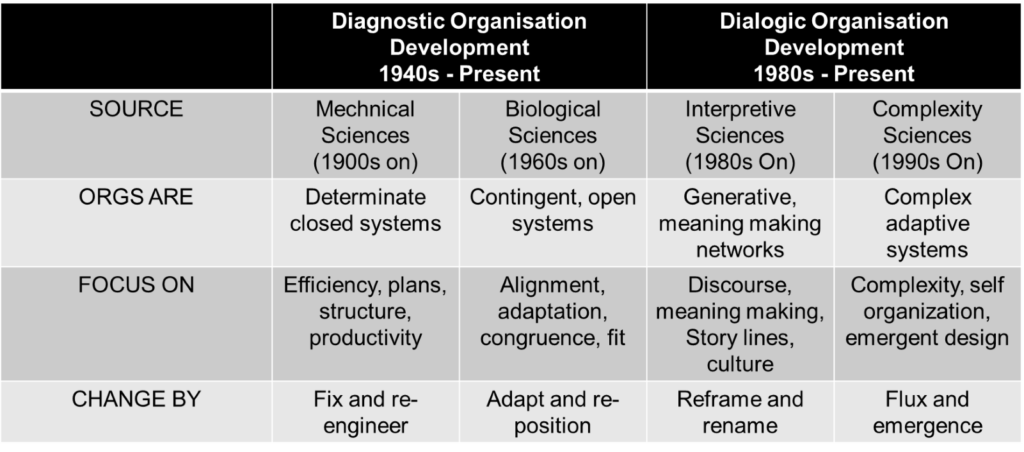

Some would question the assumption that change can be managed at all. That attempts to do so are limited at best and naïve at worst, especially in transformational and radical/discontinuous change. Discoveries in non-linear change and complexity in natural sciences have altered ideas about change and change practices. They have yielded a different paradigm from the positivism of diagnostic OD based on planned change theories of the 1940s and 1950s. Where change results from a planned process of unfreezing, movement, and refreezing through collaborative action research emphasising valid data, informed choice, and commitment.

Dialogic OD, on the other hand, considers organizations as complex, adaptive systems in a continuous process of meaning making and emergence. Where individual, group, and organizational actions result from self-organizing, socially constructed realities created and sustained by the prevailing narratives, stories and conversations through which people make meaning about their experiences. Change results not from aligning or re-aligning organizational elements, but ‘changing the conversation’ that continuously creates, re-creates, and frames understanding and action.

Here the role of the OD Practitioner is not described as a ‘facilitator’, but as a choreographer or stage manager who helps to create a ‘container’ and who hosts conversations which shape meaning making. Key characteristics of Dialogic OD are:

- Important Influences: foundational OD, social construction, complexity sciences, Appreciative Inquiry

- Organizations are self-organizing, socially constructed realities created, and changed by their prevailing narratives

- Change Theory: change emerges from disturbances that change the conversations, which shape meaning making and everyday thinking and behaviour

- Change practices: co-inquiry, collective discovery, to accelerate change by involving more and different voices, altering how and which people talk with each other. Changing conversations to change mindsets and ways of thinking that lead to new behaviours.

- Role of consultant: Ranges from the design of large-group processes that will host new conversations, to individual coaching or small-group continuous change processes.

- Core values: democratic, humanistic, and collaborative inquiry

Dialogic OD practices share many or most all of the same underlying values as foundational ‘diagnostic’ OD, which is why Bushe and Marshak consider it a form of OD and not another change paradigm. The table below shows this development over time. (Dialogic Organization Development by Gervase R. Bushe and Robert J. Marshak; Chapter Ten, The NTL Handbook of OD and Change).

Part 5 – What are the competences for working with change?

In the face of all this, what then are competencies that an OD Practitioner, engaged in Change Management, should seek to develop?

These are helpfully framed as ‘backroom and front room change matters’ by Mee-Yan Cheung Judge (Chapter 8, Organization Development, A practitioners guide for OD and HR). Here she seeks to convey the value of blending the Newtonian, OD, and Complexity and chaos theories and practice, to help practitioners gain power and influence in a traditional world of work and yet remain effective in supporting change while using the core of OD value and methods.

- Backroom matters (macro level of change work, head matters)

- Front room matters (micro level of change work, the people dimension)

All front room work is to ensure people have space and room to be part of the change process. Bringing data that others do not have, making personal sense of the change, giving a sense of agency and control over their future. Front room matters are the heart of OD practice, and OD practitioners should be at their best when applying behavioural science approaches to ensure that change, system, and people development are synonymous.

All the backroom work is to ensure the change is approached and set up in as rational and logical manner as possible – especially since all complex changes require an effectively run back office.

If we only take care of backroom matters, then we are bound to fail. You cannot drive behavioural change from the back room. If we only work with front room matters (without paying attention to the cost, risk, level of gain, and infrastructure to support the change, etc.), then we are vulnerable to stirring up passion and commitment without the capacity to carry out implementation. It is a ‘both and’ (not an ‘either or’) approach. Our competence is to excel in our ability to integrate the front and backroom matters to form a robust change plan.

Backroom Matters (head matters)

There are essential issues and understanding that require clarity before we can support the change journey.

| Becoming the client’s trusted advisor | It is important to identify those who commission change, quickly build trust and credibility, and obtain a clear brief. Well-tuned influencing skills and a couple of quick diagnostic tools, to start a conversation, help. There will often be a Programme Director or Project Manager, reporting to the client and acting as ‘gatekeeper’. Creating a good partnership with them is also key. There is also a role to support and educate clients and project boards in their role as change sponsors – active and visible sponsorship as the number one contributor to successful change [LINK]. There is a great profile of change sponsors pdf HERE from Connor Partners. |

| Developing business acumen – key questions | Mee-Yan Cheung-Judge presents a list of macro questions that capture some key areas that most leaders care about but may not find a way to articulate clearly. They can also be used as part of a collective sense-making exercise. Developing a good enough sense of the change content, even if technical in nature, lifts credibility and usefulness. What is the change about? What benefit will be gained if we achieve the change purpose? What is the minimum gain that would make this worthwhile? What scope and scale will this change be? What type of temporary change structure/resourcing will we need to support the change journey? What systemic and alignment issues will be created? |

| Knowing your way around Project Management | If your Change Management work needs to operate in a project-management environment, it is good to know your way around that discipline. The language, expectations, and what is valued is important to understand if you are to navigate it well – especially if it supports a very task-centric culture and you need to introduce a more people-centric orientation. A foundational course on LinkedIn Learning is a good start. Change can fail from poor project management. |

| Mastering the OD Consulting Cycle | The OD Cycle is our non-linear navigation map whenever we are asked to support any change process. A working knowledge will guide you through the essential phases of work and what you need to pay attention to. Wherever you start and whenever you need to loop back. Its phases could be used as an outline plan. (Organization Development, A practitioners guide for OD and HR, Section 2. Mee-Yan Cheung Judge and Linda Holbeche). |

Front Room Matters (the people dimension)

The heart and soul of change

| Getting value from stakeholder mapping | I have always felt that stakeholder mapping is undervalued. At worst, it can be a soon-forgotten tick-box exercise. At best, it forms a rich picture for a game plan to engage key groups and individuals. ‘Key’ means when successful implementation is critically dependent on whether they support the change or not. There are various methods for identifying key groups, their attitude to change, and their influence on others. I prefer mapping against a power and influence vs readiness for change grid. |

| Using Dialogic OD approaches when you can | Expert-led change efforts have a habit of ‘doing change to’ instead of ‘doing change with’. Even when this is the case, opportunities can be created to introduce approaches that create co-inquiry, collective discovery, new data to challenge assumptions, and increased ownership. Look at Dialogic OD specialism in this competency set and consider how you might use staff and customer listening sessions, roadshows, Open Space or World Café approaches, for example. Focus especially on opportunities to give voice to those who are impacted by the change or who have to manage its consequences – not just in what is done, but also how it is done. |

| Learn to engage and represent middle managers as agents of change | When it comes to the question ‘Who does change?’, the answer is not the project manager or change consultant, it is employee facing roles who are the face and voice of change. Yet, so often they get treated the same as their staff. They are the ‘mighty middle’ who can enable or sabotage the benefits of change long after the project team is gone. Middle management is a key OD priority, especially during change. Enrol them early in change planning and communication, offering training on how change impacts the people they manage, and treat them as trusted collaborators. |

| Having a working knowledge of a favourite change framework | Just as the OD Cycle will be a trusted guide through the phases of work, a working knowledge of a change framework that is people and behaviourally based can be really helpful. It can bring confidence to you, a client, and to the change team, as the content and progress of change work is recognised. It matters less which one you choose. What matters more is that it is recognized and valued by the people doing the change. My personal favourites are (at an individual level) Kubler Ross’s change curve and (at an organizational level) John Kotter’s 8 steps and Rogers’ Change Adoption Curve |

| Learn to operate from a different stand from a problem-solving mindset | Many change and project-management approaches adopt the stance of problem-solving methodologies. That people and organizations are ‘broken’ and need to be fixed. Deficit-based analysis, while powerful in diagnosis, tends to undermine human organizing and motivation because it creates a sense of threat, separation, defensiveness, and deference to expert hierarchies. Problem solving, as a means of inspiring and sustaining human systems change, is therefore limited. There are approaches that are more respectful of the good that has been inherited and invested in, and the as-yet unrealised potential that is present. Appreciative Inquiry (AI), for example, differs fundamentally from traditional problem-solving approaches. The underlying assumption is that people and organizations are full of assets, capabilities, resources, and strengths that can be located, affirmed, leveraged, and encouraged. AI offers an organization-wide way for initiating and discerning narratives and practices that are generative (creative and life giving). Look at AI specialism in this competency set. |

OD and change practitioners have a rich and varied catalogue of change theories and models to help organizations understand, explain, predict, and guide change initiatives and responses to change.