Part 1 – My coaching journey

My journey in coaching. I am often asked how I ended up in this profession – there is no short answer but I include a few steps here to prompt your own reflections.

My early career focused on supporting organizations to change, using technology (introduction of client server SAP R/3, and later the internet). We frequently underestimated the time (and budget) required to manage the ‘people aspects’ of the change process – to help individuals and teams embrace the benefits of these approaches, to embrace a paradigm shift in their thinking, and to overcome anxiety and resistance. As one of the few women in the team, these ‘soft’ areas of change often fell to me and I enjoyed the work. Also, as a young person in senior leadership, I faced steep learning curves without any of the traditional learning and development opportunities that are commonplace in large organizations today. I was hungry to learn, I valued the opportunities created and the associated challenges, but I was ‘bouncing all over the place’. A seeker, I proactively invested in many diverse personal development courses to grow personally and as a leader; in particular, my self-awareness, relationship skills, and the ability to let go and to inspire and empower others. Early childhood tragedies had exposed me to psychotherapy and I drew on insights from these experiences.

My last internal role was as VP Marketing for an incubator business in a large bank, which was a joint venture with a digital-rights management organization in the United States. When we successfully raised funds from external finance, to spin the business out of the bank, the venture capitalists insisted that all senior leaders receive coaching to support us with the transition. This was a new experience for me and I relished the opportunity to discuss my ideas and feel supported in what was becoming an increasingly stressful and rapidly changing environment as I continued to be stretched beyond my comfort zone.

Thus when the internet ‘blew up’, the organization regrouped without a marketing function, and I took the opportunity to complete my MBA at Imperial College London. I knew I wanted to start my own business but didn’t know in what. I chose to research the role executive coaching had in developing leadership competency. I had a particular interest in how it supported young leaders similar to myself who were accelerated quickly to senior roles in the IT and telecommunications sectors. This research led me to speak to over 75 organizations in the UK about how they were using coaching, and I identified a market gap.

I also met my mentor, Professor Mike van Oudtshoorn, during this time. He had just designed the first master’s degree in coaching and was looking for some business support. It was a great partnership as I was looking for someone (with more grey hair than I had at that time) to support my transition. Together we started i-coach academy. During the development of i-coach academy, I undertook further studies and completed my first doctorate in Coaching Psychology, as well as training in Existential Psychotherapy.

My hunger for further learning saw investment in numerous self-development programmes including the NTL OD programme, and coaching accreditation globally. I have now run i-coach academy for 20 years and we have delivered programmes in the UK, New York, and South Africa, as well as numerous in-house internal coach development programmes globally. I have designed and delivered executive Coaching selection and assessment processes for the NHS, Standard Bank, and others. I currently have a portfolio of executive coaching with clients and in OD consulting/Team Development projects.

I also continue to evolve i-coach academy to embrace the new digital world we live in and, in 2016, I launched a programme focused on personal reinvention – iOpening. My role has huge variety as I partner in conversation with people about things that truly matter to them, it is a privilege to be a coach.

Driving forces behind the increase of coaching in organizations

The increase in coaching has been driven by a number of organizational and societal trends. These include the globalization of business, rapid digitalization, a shift in the values and expectations of Generation Y and Z employees, and a competitive, rapidly changing marketplace (de Geus and Senge, 1997).

Organizations have responded by creating flatter, leaner structures that can react quickly to developments. However, these structures demand a different mindset and skills from managers. No longer can leaders rely on their expert knowledge or hierarchical power; in today’s increasingly complex and fast-moving world, the paradox is that to be an effective leader, you need to let go of your expert knowledge and instead create space for others to perform and learn. To put it simply: Adopt a coaching mindset. These trends also mean that it is less about what we know and more about how we learn. This is what differentiates the individuals, teams, and organizations that both survive and thrive. Coaching, as an intervention, is core to building the capability and capacity to learn, whether it is delivered by internal coaches, external coaches, OD professionals, HR professionals, or leaders.

What exactly do we mean by coaching?

Coaching is, at its core, a learning conversation in which the client is at the centre. A coaching conversation enables learning by identifying new perspectives, unlocking ideas, and building confidence. Crucially, it enables clients to unlearn outdated mindsets, behaviours, and strategies, so they can be effective and live a life that feels truly meaningful to them within an ethical and value-driven framework. Coaching is rarely positioned as remedial; rather, it is a development-focused intervention that does not aspire to ‘fix’ people.

The task of coaching is different to mentoring, teaching, facilitation, consulting, assessment, counselling, and therapy. However, it does draw on a number of disciplines. A coaching mindset can add value to an intervention without it becoming formal coaching or without the need for a professional coach. For example, a line manager does not have to be an accredited coach to unlock learning and potential in their team; nor does a consultant or mentor need to be an accredited coach to build their role of trusted advisor with their clients. The core requirement is for them to adopt a coaching mindset, to believe and trust the coaching process, and to integrate foundational skills, such as active and deep listening, powerful questioning, and incorporating feedback into their conversations.

What is the role of coaching?

The Witherspoon and White typology (1997) is one way to categorize how coaching is used in organizations. These include coaching for skills, coaching for performance, coaching for development, and coaching for the executive agenda. In my mind, all of these interventions require a coaching mindset, but not all require a formal professional coaching intervention. So, for me, building one’s coaching mindset and skills is different than developing as a coach. A coaching mindset is a vital ingredient for organizations that aim to learn and evolve as they navigate through cumulative complexity.

Coaches need to differentiate the purpose of their work – whom it is for and what it delivers. There are numerous opportunities for the application of coaching. For me, one is not ‘better’ than the other – they are just different. I do not believe that executive coaches are better coaches than coaches who work with first-level managers, and with teachers, teenagers, or parents. Rather, the work is different and requires different underpinnings, experience, and processes. At i-coach, we support each coach to articulate their own coaching framework – and there may be more than one. This approach acknowledges the diversity of coaching and discourages coaches from attempting to be all things to all people. In the same way, I encourage Organizational Development (OD) practitioners not to feel that they have to be coaches, in order to use coaching to add value as part of an intervention, but to acknowledge the difference and to establish appropriate boundaries that reflect the two hats they may wear in any intervention. (You can read more about my view on the difference between OD and coaching in the extra material).

What differentiates ‘good’ from ‘great’ executive coaches?

I am often asked this question as are others in the profession. Below I share my opinion, formed by working in the field for 20 years as an executive coach and educator who has trained and supervised coaches at a variety of stages of their careers and in numerous places around the world. My perspectives have additionally been shaped through the design, development, and delivery of assessment centres that assess executive coaches as part of a selection process to join large organizations in the UK and South Africa. My view is thus informed by my values, education, and experience – and it is one view, not fact. The view below, also, is tailored to coaches working with Senior Leaders/Executives

- Top of my list – great coaches work on themselves. They understand that they are the primary instrument in coaching. They have invested years in therapy, training, and personal development in order to get under the surface of who they are as human beings – to understand their strengths and patterns, as well as their triggers. They not only have the awareness of these, but they also know how to work with these aspects of themselves and to process them in order to be resilient in their work and to protect their clients.

- They understand their role is one of privilege. A role that requires a strong ethical framework. They appreciate that coaching is a partnership where clients trust them with information and perspectives that are unique and that matter deeply. They hold the individual with unconditional positive regard and respect. They understand that, while you can never truly understand someone else’s perspective, you can work to get closer to it and help clients to hear and see themselves.

- They are comfortable in their own skin, grounded and present. They truly trust the coaching process and adopt a coaching mindset. They don’t feel hooked to ‘fix’ the client or to perform. Saying this, they don’t always feel confident and adrenaline is used as fuel to remain sharp and attuned to this important work. These coaches know their limitations and know how to confidently hold space for a client. They recognize that coaching is not about them and they leave their ego at the door.

- They are seekers at heart, curious and keen to learn about lots of things. They invest in all types of learning, are hungry for feedback, and open to learning. They are critical reflectors and have strong reflexive skills that they use, in the moment, to enhance their coaching.

- They are exceptional listeners – listening deeply both to what is said and what is unsaid. They have presence and use their energy and intuition for the benefit of clients, holding their observations lightly for clients to consider and explore, rather than feeling judged or analysed.

- They ask powerful questions that are tailored to the client’s story and that act as catalysts for their thinking.

- They bring challenge to the conversation and understand that learning is not always comfortable. They have the skills to know when and how to challenge in a way that can be received by their clients. They partner with their clients when resistance appears.

- They think systemically and understand the interrelational nature of relationships and systems; and they work to hold complexity and paradox, supporting their clients in building their capacity to see the connections and to make choices that empower them.

- They understand learning theory and are skilled at supporting clients to not just resolve issues, but to learn about WHO they are so that they can sustain their learning beyond the coaching intervention; and to self-coach and, in some instances, to coach others.

Part 2 – Core competences for coaching

When asked, ‘What is the core standard for coaching?’ or ‘What do people who are competent demonstrate?’ I am keen to draw your attention to the evolution of professional standards in the field of coaching over the last 20 years. While the coaching profession is still young, there are two professional bodies in this field: the International Coaching Federation (ICF) and the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC), who have invested in researching competency frameworks and setting standards over the last 20 years. They also proactively accredit education providers through their programmes and offer credentials to individuals. These benchmarks help organization clients to differentiate coaches’ experience and competence without investing in their own assessment processes. I have mapped these criteria in the grid to prompt your thinking as you consider what to include in your own development plan. I also include the ICF and EMCC ethics statements and links to their full competency maps, below the grid, for your reference.

It is important to note that there are numerous other professional bodies (e.g. Association for Coaching, APECS, Special Group in Coaching Psychology, World association of business coaching etc.) and competency frameworks. However, these are the two professional bodies that I work with most frequently and with whom I have chosen to accredit i-coach academy’s education programmes. I also hold individual credentials with both the ICF and EMCC.

I have also shared the competencies developed to support i-coach academy’s assessment of coaches through the years since our first master’s programme in 2002. I have included the recent set for you to consider and would draw your attention to two in particular. One of i-coach Academy’s core contributions to the field was the early articulation of ‘building the capacity to learn’ and ‘self-presentation’ as criteria. A number of frameworks now integrate a version of these, especially the ‘building capacity to learn’. In i-coach’s view, exceptional coaches have the ability not just to help a client solve an issue but to help the client learn about who they are, what works for them, how they learn, how they work, etc. These lenses help to reduce the dependency on the coach as they build their skill to self-coach and, when mastering the coaching skillset, the one-to-one coaching relationship can build the capacity of the client to adopt a coaching mindset and to approach in other conversations without ‘coaching skills training’. Thus, one-to-one coaching, with a skilled coach, has the power to shift the system too.

‘Self-presentation’ goes back to what I described earlier about the i-coach coaching framework and the value of being able to articulate your approach so that you can truly partner with clients and empower them. This congruence between who you are, what behaviours you adopt, and what you say you are is important for the client and is a critical part of coach development. Akin to stages of adult development, developing as a coach requires a grounded sense of belief and, paradoxically, at times a lack of confidence that evokes a humble, curious stance and ensures a sustainable ethical frame.

Finally, please do not assume that as a great executive coach, working with individuals, that you will be equally skilled at team or group coaching or as a coaching supervisor. All of these roles have nuances and benefit from different theoretical frameworks/underpinnings and experience. This contribution for the app focuses on individual coaching as its priority.

Part 3 – Options for development

There are numerous opportunities to develop as a coach and to build a coaching mindset and the associated skillset. I have made some suggestions below to get you started and if you want to learn more, perhaps join one of i-coach’s free webinars. In these webinars I share my research and talk about the different accreditation options and the nuances in different regions and markets. I also offer information on the i-coach programmes. Visit our website to register for events including “Could you be a Coach?”

Another good place to source programmes, if you want to become an accredited coach, are the professional bodies’ websites. As discussed, the two we align with most are the ICF and EMCC, and you can see a variety of the organizations’ programmes and their associated accreditation level or credential options here:

- https://apps.coachfederation.org

- ICF – Find A Training Program (coachingfederation.org.uk))

- EQA Holders – EMCC Global

Getting Started

- I encourage you to self-assess against the competency grid and to perhaps consider the type of coaching you are keen to deliver. Do you want to be a professional coach working with executives in organizations, or to use a coaching mindset and skills to enhance your role as a consultant, HR business partner, therapist, parent, or leader? This decision is crucial to your choice of development path and informs whether accreditation is a must-have or a nice-to-have. It will also impact the level of your investment in time and money.

- If you have been coaching for a while but have never had any formal training or applied for accreditation before, please note that in my experience the learning journey for you may, in fact, be harder. Learning to unlearn all you have developed through experience, in order to reconstruct this for a more specialized focus as a professional coach and to meet the external benchmarks, is likely to see you lose confidence initially; however, do not be put off from taking the leap and developing yourself and your practice further – you will come out much stronger and clearer about who you are as a coach and, in turn, add even more value to your clients. You may find this statement from my doctorate research interesting to browse, as it is a synthesis of the experience of developing professional coaching practice.

A few practical tips

- In my mind, the key shift in beginning your journey as a coach is to let go of needing to be an expert. There are numerous ways to develop this, but perhaps start by assessing yourself. How often do you need to be in control? What happens when you lose control? When you are not the most experienced or skilled person in the conversation? How do you feel? What behaviours does it elicit? How comfortable are you with silence?

- Another area to consider are your listening skills – start with active and deep listening and then revisit the core techniques of reflecting back, paraphrasing, and summarizing. Hone and develop your ability to notice what is unsaid.

- Think about how you build relationships. There is strong evidence to suggest that the relationship between coach and client is critical to the efficacy of coaching. What do you notice about how you establish and maintain relationships? Do you have a repertoire to work with all types of people, or do you find some clients more difficult to work with than others?

- Finally, remember that coaching is about ‘doing it’, so the best way to learn is to coach – not just to read about coaching – so find some colleagues to practice with, ask for feedback, set up a learning trio, invest in a supervisor or take a course. Experiential learning is essential.

Part 4 – What is the difference between OD and coaching? If any?

OD and HRD practitioners view coaching as a part of their respective fields rather than a distinct skillset. Research (Hamlin, Ellinger, Beattie, 2009) suggests that all three fields of practice are very similar in intent and process. From their examination of 29 definitions, a composite perspective of OD was derived: Organization Development is any systematic process or activity which increases organizational functioning, effectiveness and performance through the development of an organization’s capability to solve problems and bring about beneficial change and renewal in its structures, systems, and culture, and which helps and assists people in organizations to improve their day–to-day organizational lives and well-being, and enhances both individual, group, and organizational learning and development.

From my perspective, it is the coaching mindset that differentiates the application of OD, HRD, and coaching that is distinct. All practitioners may focus on similar themes; however, their intervention style and approach make a difference.

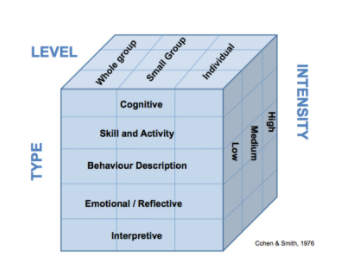

OD practitioners intervene at different levels of a system and in different ways to unlock organization effectiveness. They flex between intrapersonal and interpersonal, group and unit, thinking holistically to unlock potential. Coaching practitioners are more focused on individuals and teams for a variety of purposes and, while they may work with individuals and groups simultaneously, they frequently own the intervention for the whole system. My experience is different coaches working with different clients, for different purposes. The thread connecting them is the coaching mindset and philosophy with which they approach the work. A mindset that believes the individual is resourceful and has the answers within them, and a mindset that helps the person not just to problem-solve the issue in front of them, but also to learn about themselves and build their capacity as a learner(s) so they can adapt and address future challenges with greater ease.

While some may see coaching as an individual process, working towards behavioural change, from my perspective, unless the individual or group is addressed as part of the system in which they belong (family, organization, community) then the change is unlikely to sustain and may cause more harm than good. As the systemic perspective is central to OD, OD practitioners bring this systemic lens to their coaching work.

Another concept that overlaps between coaching and OD is the use of self. In my mind, the best coaches are those that have done a lot of work on themselves. They understand that they, as coaches, are the primary instrument in the effectiveness of their coaching intervention and that, while coaches can all use the same tools, each coach is different. It is therefore similar to therapy training and OD training, amongst others. Effective coach development focuses significantly on self-awareness and personal development – not exclusively on skills, tools, and techniques.

The competency maps will prompt your own views on what is the same and what is different. From my experience, the key differences are:

- OD practitioners need more technical understanding of organizations and systems than coaches, as well as a broader toolkit of interventions to take ownership of the whole system.

- OD practitioners need to be skilled at interventions for all levels of the system and to have the capacity to hold the whole, while coaches can focus on the individual or the group/team.

While I value a systemic lens to coaching, this is not universal and so OD practitioners may well have a more systemic approach than some coaches. This applies to levels of listening, too, for as coaches will be skilled listeners of the said and unsaid, their ability to listen to the system and elicit insight about the context may be less of a focus for some coaches.

- Boundaries and ethics are crucial to both roles, and there are different perspectives on what is ‘ethical’ practice across a number of dimensions linked to the philosophy of OD vs. coaching. One example is the value of expert knowledge and how best to integrate this with clients, in contrast to unlocking their own wisdom and ideas – or who the client is – whether it is an organization or individual. Also, coaches typically do not have long-term, open-ended contracts with clients. Their ‘goal’ is to make themselves redundant, over time, and to build capacity in the client – individual or team.

- OD practitioners have to be chameleons that adjust to the needs of the system, to provoke it and, when required, to bring high levels of challenge that demand unique levels of personal resilience. Coaches can choose to focus their practice on areas that require less-direct confrontation. It is important for coaches not to worry about what others think, in order to maintain neutrality and to avoid collusion with clients. For OD practitioners, however, it is essential.

- The level of personal work, self-awareness training, and insight in becoming a competent practitioner, who is alert to triggers and possesses the confidence and skill to self-manage and stay grounded, is a crucial skill across both roles.

- OD practitioners and coaches are likely to be curious and learners at heart. Coaches, however, are encouraged to constantly invest in their professional development. They are required to receive supervision for their work in a similar way to therapists and counsellors. While many OD professionals invest in reflective practices – learning groups and shadow consulting – these practices are less established, with fewer formal expectations than in the field of coaching. Given the ‘duty of care’ that both of these roles hold, the opportunity to pause, reflect, and sense-check is part of the ethical framework that is core to both roles.

- The learning mindset and a focus on enabling the client to learn, as the primary goal, is more embedded in the role of coach than OD practitioner where, frequently, the task can be more the focus than the learning or development outcome. Coaches are attuned to supporting cognitive, emotional, and somatic development wherever possible.

Part 5 – Coaching and OD Competences Map

| ICF Coaching competences | EMCC Coaching competences | i-Coach Academy coaching competences |

| A. Foundation 1. Demonstrates Ethical Practice DEFINITION: Understands and consistently applies coaching ethics and standards of coaching 2. Embodies a Coaching Mindset DEFINITION: Develops and maintains a mindset that is open, curious, flexible, and client-centred B. Co-Creating the Relationship 3. Establishes and Maintains Agreements DEFINITION: Partners with the client and relevant stakeholders to create clear agreements about the coaching relationship, process, plans, and goals. Establishes agreements for the overall coaching engagement, as well as those for each coaching session 4. Cultivates Trust and Safety DEFINITION: Partners with the client to create a safe, supportive environment that allows the client to share freely. Maintains a relationship of mutual respect and trust 5. Maintains Presence DEFINITION: Is fully conscious and present with the client, employing a style that is open, flexible, grounded, and confident C. Communicating Effectively 6. Listens Actively DEFINITION: Focuses on what the client is and is not saying, to fully understand what is being communicated in the context of the client systems and to support client self-expression 7. Evokes Awareness DEFINITION: Facilitates client insight and learning by using tools and techniques, such as powerful questioning, silence, metaphor, or analogy D. Cultivating Learning and Growth 8. Facilitates Client Growth DEFINITION: Partners with the client to transform learning and insight into action. Promotes client autonomy in the coaching process | Competence categories 1. Understanding Self Demonstrates awareness of own values, beliefs, and behaviours; recognises how these affect their practice, and uses this self-awareness to manage their effectiveness in meeting the client’s and, where relevant, the sponsor’s objectives 2. Commitment to Self-Development Explore and improve the standard of their practice and maintain the reputation of the profession 3. Managing the Contract Establishes and maintains the expectations and boundaries of the mentoring/coaching contract with the client and, where appropriate, with sponsors 4. Building the Relationship Skilfully builds and maintains an effective relationship with the client and, where appropriate, with the sponsor 5. Enabling Insight and Learning Works with the client and sponsor to bring about insight and learning 6. Outcome and Action Orientation Demonstrates approach and uses the skills in supporting the client to make desired changes 7. Use of Models and Techniques Applies models and tools, techniques and ideas beyond the core communication skills in order to bring about insight and learning 8. Evaluation Gathers information on the effectiveness of own practice and contributes to establishing a culture of evaluation of outcomes | Practitioner-Level competences Establishing and Maintaining the Relationship Ability to quickly establish confidence, trust, and respect between oneself and a wide range of clients in different situations, as well as maintaining strong, empowering relationships Managing the Contract and Boundaries Evidence of a coaching mindset and activities that enable the articulation and maintenance of a clear contract that reflects the expectations of both client and coach. Also, the coach’s ability to maintain their stated boundaries and ethical code of coaching practice, and a recognition of the limits of their own competence when agreeing to client engagements Identifying Issues Effectiveness in supporting the client to analyse situations, secure relevant information, and enable insight to identify the client’s core issues Building Capacity to Learn Actively developing the client’s ability to learn (to self-coach and coach others), ensuring sustainable learning and non-dependence Interpersonal Sensitivity Coach’s ability to demonstrate awareness of their impact on other people and skill in tuning in to the feelings and needs of others Congruence and Self-Presentation Coach’s ability to understand the impact of their values, beliefs, diversity, personal history, and preferences on their work and their ability to authentically represent themselves as a congruent, credible professional to their chosen client group Self-Appraisal and Evaluation Active engagement with feedback, supervision, development activities, and reflexive learning processes that enable insights likely to ensure continuous enhancement of their coaching practice, personal awareness, and understanding Mastery Level – Managing Emotions and Ambiguity Ability to contain, hold, but not shut down emotional reactions within the boundaries of coaching, and to demonstrate and develop stability of behaviour under stress, opposition, and ambiguity Mastery Level – Organisational and Environmental Sensitivity Taking actions that indicate recognition of the key systems/relationships, and demonstrates awareness of the implications of decisions and activities on other parts of the organisation/system. Also, supporting clients to extend their awareness beyond immediate systems, to consider influences from the wider environment |

| ICF ethics: ICF Code of Ethics – International Coaching Federation (coachfederation.org) | EMCC ethics (this is a Global Code of Ethics that both EMCC and AC have signed up to (Global Code of Ethics: Download the Code | Global Code of Ethics) | |

| ICF competencies: The Gold Standard in Coaching | ICF – Core Competencies (coachfederation.org) | EMCC competencies: Competence Framework (emccuk.org) |